|

|

Subject: Save Our Holy Water

Journal: The Times Date: September 1994 Author: Clive Fewins

Hundreds of long-lost holy wells around Britain are waiting to be rediscovered.

If Bradford City Football Club wish to increase their chances of promotion this season, they could do worse than look for

inspiration below their ground. For somewhere underneath the turf near the Ash Lane end is a long-covered holy well, famed

in medieval times for its curative powers. Local historian Valerie Shepherd rediscovered the site when writing a book on

the historic wells of Bradford, but has no idea when it was finally sealed – and she has no intention of turning up during

a home game with divining rods and a spade.

Mrs Shepherd is one of the growing band of enthusiasts keen to record Britain’s holy wells for posterity. There is no

national record of all the sites and many hundreds are yet to be found, according to Tristan Gray Hulse.

Mr Gray Hulse, 48, a former Benedictine monk, and Roy Fry are the editors of Source, a journal about holy wells,

which reappears this month after a four-year gap. Mr Gray Hulse lives near St. Asaph in North Wales and estimates that there

are 1,100 known holy wells in Wales alone. In Cornwall, researcher Paul Broadhurst knows of at least 250 holy wells in the

county, and says there are “many hundreds” still to be rediscovered.

On the August day when I visited the Cornish St. Euny’s well, almost buried beside a rough track through high scrub country

a few miles inland from Penizance, a lone woman knelt deep in prayer. Few tourists discover the well, only four miles as

the crow flies from the much-visited St. Madron's well near Penzance. The well – like many others it is said never to have

run dry – lies at the end of a winding path throngh thick woods of blackthorn and alder. Near by lies a small ruined well

chapel where baptisms were performed and the sick were brought to the altar. The chapel became a place of pilgrimage by

thousands after the miraculous cure in 1640 of John Trelille, a poor cripple who all his life had been forced to walk on

his hands until he was cured by the waters of the Madron well.

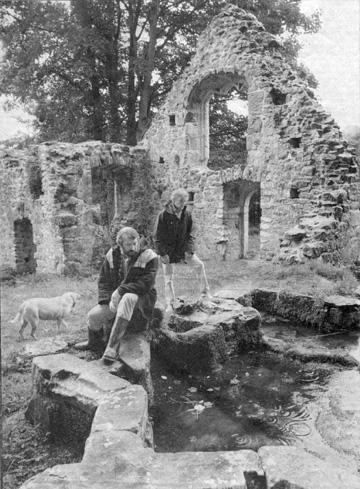

Picture: Howard Barlow  Tristan Gray Hulse (left) and Roy Fry at St. Mary’s holy well, Wigfan; there are more than 1,100 such wells in Wales.

Rags, pins, flowers and pieces of jewellery hang from bushes around the well – survivals of the ancient custom of leaving

votive offerings to the residing spirit that supplies the water and who must be appeased if the flow is to continue

uninterrupted.

In pre-Christian times, any spring where the life-giving waters of Mother Earth came out of the ground was likely to be

worshipped, and the spot made “holy”. When Christianity reached our shores Celtic converts rededicated their holy wells,

which explains the survival of so many of them.

Most of the holy wells in Cornwall are visited regularly, both for their curiosity value and their religions significance.

People who come to scoff often stay to ponder, overawed by their sheer age and sense of mystery; others leave a votive

offering. Many Christians regard the wells with a cautious unease. The feeling was summed up by the late Daphne du Maurier

in a paragraph on St. Madron's well in her book Vanishing Cornwall.

“We found it at last ... in a clearing within stone walls. The water was dank and still. I was not satisfied. This must be

the baptistry, spoken of in later books. I sought the magic healing spring itself, which should rise from the ground clear

and never stagnant, bubbling out of unknown depths. A trickle of water underneath a stone a few yards distant, and in the

profoundest tangle of the thicket, made me rejoice ... breaking off a twig I turned it nine times against the sun ...”

In the Derbyshire dales the old-established custom of well dressing, in which the wells are decorated with flowers, in the

season following Ascensiontide, is now regarded more as a tradition and an art form than as a custom with deep religious

significance. Dressed wells, which retain their floral magnificence for much of the summer, feature strongly in tourist

literature promoting the area.

Nevertheless a number of holy wells still play their part in mainstream worship. The most famous is St. Winefride’s, at

Holywell on the coast of Clywd, the only Roman Catholic shrine of its type to have escaped destruction during the

Reformation. Since about 1510 the well, which has drawn pilgrims since the seventh century, has been covered by a

magnificent late perpendicular stone structure built by Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry Tudor, later Henry VII. Until

the 1960s crutches used to line the walls of the building. The priest, Father Bernard Lordan, makes no great claims for

the waters. He takes the view, commonly held today, that many of the people who come in search of a cure are probably

in a susceptible frame of mind – ideal circumstances for the body’s own self-healing powers to be stimulated.

“Nevertheless after six years here my scepticism falls away when I hear some of the tales of people who come here in

a spirit of great faith, and claim to have been cured,” he said. “Somehow or other the finger of God has touched this

place in a remarkable way.”

At Anglican churches such as Stogursey in Somerset, water is regularly drawn from the local holy well for use in

baptism and other rituals.

The logicality, the evenness and the interdependence of all the parts of the craft upon one another all add to the appeal

of the process. It was summed up well by the oldest member of the course. Clifford England, a 79-year-old retired engineer

from Bedfordshire, when he described the design as based on good engineering principles.

Mr Cray Hulse said: “Despite the renewed interest in preserving and recording our British holy wells in recent years

increasing numbers of them have been filled in.

“Many are little more than nettle-covered holes in the ground, almost lost in the countryside. Source will

encourage the formation of local groups to seek out and help to preserve well sites.

“Our local history group recently managed to persuade CADW – the Welsh equivalent of English Heritage – to restore

the remains of an ancient chapel adjoining our local holy well, which is dedicated to St. Mary. This is the sort of

grassroots action we wish to encourage.”

|

|||||||

| © 2006–2026 Clive Fewins. All rights reserved. | Site designed by Ridgedale Communications Ltd. | |||||||||||||||||||||