|

|

Subject: Well-kept Secrets In The Malvern Hills

Journal: The Times Date: December 1994 Author: Clive Fewins

Malvern: From the surrounding hills gushes the product that brought prosperity to the town.

“Can we dig up your garden” the couple at the door asked Ron Mason.

“Sure, but you’ll need a pickaxe to remove the paving stones and a long ladder if you locate the tank,” said Mr Mason with

a smile on being offered an explanation.

Illustration: Mary Evans

In Victorian times, St. Ann’s well was the most popular gathering place for patients at hydrotherapy establishments in Malvern. The house and extension are now listed buildings.

Malvern’s most curious duo had found another convert in their attempt to track down the hundreds of springs, spouts,

fountains and wells that have their origin in the hills from which the town takes its name.

The excavation duly took place and, beneath the slabs and a shallow layer of earth, the pair found a brick-built,

barrel-vaulted, Victorian water tank big enough to hold a dozen people standing up.

“Climbing down into the tank was a frightening experience, though since then we have found two twice the size,” said Cora

Weaver, a teacher and local history enthusiast.

Mrs Weaver and Bruce Osborne are the authors Aquae Malvernensis, a lively new guide to the many water sources that

in the last century made Malvern a watering hole for the rich and famous.

Tourists still come to Malvern, but more to walk the 100 miles of paths that criss-cross the hills and to enjoy the

countryside than to savour the history of the town’s most famous product – its water.

This is curious; after all, this is the water the Queen takes with her in bottles whenever she travels abroad. All the

visitor needs in order to take home as much as he or she wants is a supply of bottles. Mrs Weaver and Mr Osborne say there

must have been some 24 bottling plants in the hills at one time or another. Now there is just one, the source of water

bottled by you-know-who and marketed worldwide.

So runs the line, famous in the town, about one of Malvern’s most distinguished adopted sons. The son of a Worcester

tradesman. John Wall studied medicine at Oxford in the early 18th century and is credited with being the founder of the

“water cure” that brought prosperity, and people, to the town between 1840 and 1880.

The story of how the craze for good health led to the great boom that finally petered out at the beginning of this century

is a fascinating one. But to Mrs Weaver and Mr Osborne, the real interest is in the detective work needed to track down

the legacy of the water cure and go back to the sources known in medieval times.

The water cure was a Victorian phenomenon that comprised wrapping the patient in a long, wet sheet, and covering them with

blankets and an eiderdown. Only the head was left uncovered. After an hour the patient was unwrapped, placed in a shallow

bath and showered with cold water. The patient was then rubbed down with a towel before dressing again. The treatment,

repeated each day br a week, was designed to stimulate circulation, cleanse the body of impurities and to reduce stress.

In between patients were encouraged to walk the hills.

What was the first spa building is now Lloyds Bank; the later one, Holyrood House, is now attached to the Tudor Hotel.

The water-cure establishments were run by a clutch of welI-known doctors – Gully, Wilson and Grindrod among them who

wrote entertainingly vitriolic letters about each other's methods to the Malvern Advertiser.

In the course of their research, Mrs Weaver and Mr Osborne have rediscovered a number of long-lost springs, and the

book contains details histories and descriptions of 60 of them.

“Malvern water claims to be unique in having no mineral content”, said Mrs Weaver. “The reason is the fast movement

of the rainwater through the steep sloping granite hills. Because it flows very rapidly through the fissures and crevices

in the rock it does not absorb minerals.”

Today the enterprising tourist can walk, cycle, or drive to see such curiosities as St. Ann’s Well or Holy Well. They

can fill up for free at the latter or at the delightfully-named Evendine spring, or they can seek out the village of

Colwall, where Malvern water is still bottled.

Those with a more esoteric interest might want to track down, the many examples of containment such as the tank under

Ron Mason’s garden. It is the beneficent work of Charles Morris, a London developer who loved Malvern and paid for three

schemes to harness springs.

It is all sealed away again under Mr Mason’s garden now and hard to visualise. Nevertheless, Mrs Weaver and Mr Osborne

estimate there must be at least a dozen such installations under the turf and bracken of the nine-mile chain of hills.

“The Victorian engineers were keen to regulate sources so that they had a regular supply of water from the hills for

the town,” Mrs Weaver said.

“There is a huge underground network of tanks and pipes designed to contain and regulate springs. The Victorians, with

their colossaI energy, must constantly have been digging up the hillsides above the town. We often wonder how many of

these networks we still do not know about.

“One reason for this work was that despite the fact that Malvern claimed to have the purest water in the country, it

also suffered from drought. The fast run off from the hills meant that in dry periods there was a real water shortage.

So ironically, in 1871, Malvern became the first place in the country to have water metering installed."

One of the most famous of Malvern’s “regulated springs” is Hay Slad. Ostensibly it is just a prolific spring that

gushes forth at the rate of five gallons a minute. But in fact it is a good example of Victorian containment. Buried

in the hillside at the rear is a 100,000 gallon reservoir, hewn out of the rock in 1893 and still functioning. It has

helped to regulate the flow ever since.

On the autumn day I visited Malvern, people from as far afield as Bromsgrove and Bristol were filling up large

containers at Hay Slad to take home with them. One man I met, Michael Holt, regularly makes the 140-mile return trip

from his Bristol home, returning with 5O litres of free Malvern water every time. “It lasts us a month. The water in

Bristol is not even fit to make a cup of tea with, let alone drink,” he said.

An irony is that unless the people of Malvern go to one of the springs with containers and fill up and many do they

have no access to their own water. Since a new main was installed in the main town two years ago all their water comes

via the Severn-Trent network.

“lf they want to be sure of drinking fresh Malvern water, local people have to fill up bottles from one of the three

functioning public spouts,” Mr Osborne said. “Surely it is not asking a great deal for the town of Malvern to extend

and renovate its spouts? At the very least it would be a wonderful tourism opportunity.”

• Aquae Malvernensis (£9.99 inc. p&p, from Cora Weaver, Hall Green, Malvern, Hereford and Worcester WR14 3QX).

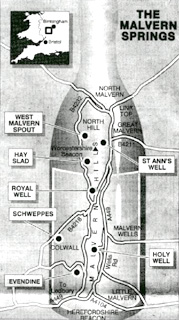

The prolific spring at Evendine is a popular filling station for locals and visitors. The following circular tour of some of the principal springs and spouts is a ten-mile drive. The grid references refer to Ordnance Survey Landranger map sheet No 150. From the junction in the centre of Great Malvern where the B4211 joins the A449 turn right and almost immediately left into St. Ann’s Road. Park and follow the signposted footpath up to the ancient St. Ann’s Well (grid ref 77214580). In Victorian days, the well was the most popular gathering place for patients at hydrotherapy establishments in the town. Back in the car, rejoin the A449 and at Link Top take the B4232 through North Malvern for about a mile and a half to West Malvern Spout (76404595). This now dry spring ia adjacent to the shop and post office run by Ron Mason, who might explain its interesting history if he is in the shop. Drive on about half a mile to Hay Slad (76654480). This is a large, constantly-flowing spout on the left side of the road as you head south along West Malvern Road. It is often crowded with locals and visitors filling up containers. Half a mile further on, again on the left side of the road is the The Royal Well (76624427), otherwise known as St. Thomas’s Spring. The water from this spring was once regarded as the purest in the Malverns. Nowadays it is only a trickle. After another quarter of a mile you will reach the road junction at The Wyche cutting. Here take the B4218 towards the village of Colwall. About a mile along on your left-hand side you will see the Schweppes bottling plant near the railway station (756425). Return up the B4218 to The Wyhe and turn sharp right. About a mile and a half along is Evendine spring (7664099). From Evendine follow the road round Wynds Point where it joins the A449. Turn left. After half a mile take a left fork up Holy Well Road. About half a mile on right on a hairpin bend is the Holy Well (77034233) on your left. The present building, from 1843, was based on a design from the German spa of Baden-Baden. Drive along the A449 for two-and-a-half miles in the same direction until once more you reach the centre of the town. • WALKS: The Malvern Hills are criss-crossed with walks affording magnificent views. The best way to walk them is to call at the Tourist Information Centre (0684 892289 open 10am-5pm Monday to Saturday) in Grange Road in central Malvern and buy a set of three 1:10,000 scale walking maps of the Malvern Hills (£3). Here are three of my favourite walks. • The Worcestershire Beacon. Begin at the car park in the Beacon Road at the Wyche Cutting. There is a metalled path along the one-mile route to the beacon, the highest point in Malvern chain. For a more circuitous route refer to the maps, sheet one. • From the Jubilee Drive car park opposite the Kettle Sings teashop. Follow any of the marked routes on sheet two of the set of maps. • The Herefordshire Beacon (otherwise known as The British Camp). Park at the large car park at the foot of the beacon and take the well-signposted route to the British Camp. The return route is two-and-a-half mile. For a more circuitous route refer to the set of maps, sheet three. |

|||||||

| © 2006–2026 Clive Fewins. All rights reserved. | Site designed by Ridgedale Communications Ltd. | |||||||||||||||||||||